See a cross currency market like USD/JPY, EUR/JPY, and EUR/USD, so that you can evaluate which is cheaper and which is more expensive.

e.g., EUR > USD > JPY (depreciation)

Question:

Why does JPY move in a large scale?

Answer:

(1) Japan's short- and long-term interest rates are one of the lowest in the world.

(2) Japan has one of the biggest financial / capital markets, there are lots of investors / business entities, and it is relatively easy to borrow money.

(3) Japan is one of the biggest current-account surplus countries with a floating foreign exchange rate. (China is no.1 in the current-account surplus, but it is not a floating rate. Also, technically trade surplus of Japan is important rather than income balance surplus, which could be re-invested in the same country.) General business entities sell foreign currencies and buy JPY on a regular basis apart from financial institutions. This creates a constant buy-JPY pressure; when financial institutions also buy JPY (or hedge) to decrease their position, then JPY appreciates more than usual.

Furthermore, Japan is the biggest net lender (creditor) country; it has a huge foreign currency exposure.

On the contrary, the U.S. is the biggest net borrower (debtor) country with the biggest current-account deficits in the world.

Given the reasons above, JPY and USD sometimes move differently. (1) When economic slowdown, stock markets declines, and people are risk-averse ("risk-off"), USD is bought back together with JPY. JPY has a constant buy-pressure by current-account surplus, so it would appreciate more than USD. (2) When "risk-on", JPY needs to have larger foreign investments in order to deprecate against USD.

Question:

What makes a currency get appreciated or depreciated?

Answer:

In the short run, the higher (lower) interest rate, the more appreciated (depreciated).

In the mid run, a "one-way" direction of international money flow with (1) trade, (2) securities investment, and (3) direct investment without "hedging" are important.

In the long run, the higher (lower) inflation rate, the more depreciated (appreciated). The Purchase Price Parity (PPP) works for a long time, 10-15 years; in the short / mid term, currency markets move above or below a PPP-indicated FX rate. A currency in a inflationary (=price increasing) country depreciates while a currency in a deflationary (=price decreasing) country appreciates. Price increasing (decreasing) means currency depreciation (appreciation).

We have to look at a nominal and real "effective" foreign exchange rate. That is weighted by using the money amount of trade (import/export). If you look at JPY, it is an exchange rate vs other 60+ countries' currencies, including 15+ Euro countries.

If you look at nominal foreign exchange rate, it moves along with inflation rate differential. For real rate, it moves above and below the long-term equilibrium rate.

Currency Market Size (April 2010, per day, trillion USD)

Spot = 1.5

Forward = 0.5

FX swap = 1.8

Option and others = 0.3

Total = 4.0

Market share of the total figure above (4 trillion USD)

EUR/USD = 28%

USD/JPY = 14%

GBP/USD = 9%

...

EUR/JPY = 3%

Market share of spot trading (total = 200%)

USD 79.7%

EUR 46.4%

JPY 20.1%

GBP 14.3%

AUD 7.5%

CHF 6.2%

CAD 5.2%

NZD 1.5%

SEK 1.3%

NOK 0.8%

Source: BIS

Japan: current account surplus, creditor

US: current account deficit, debtor

Japan and US are totally opposite in the two aspects above. However, both countries are capital providers and JPY and USD are currencies to borrow to invest. When risk-off (e.g., global economic slowdown, stock price decline, or catastrophe), both JPY and USD are bought back, but JPY usually appreciates against USD because Japan and US are current account surplus and deficit, and creditor and debtor, respectively.

Players in currency markets are financial and general business (e.g., automaker); general business players usually buy or sell currencies without a speculative view. That could create a constant one-direction demand and supply. Financial, speculative players usually build a position so that they can make a profit after an important announcement like the US labor market figures. After the announcement, they close (buy back or sell) their positions and it creates a demand and supply in a currency market. It is very important to understand that speculative players positions are built BEFORE an announcement and it is closed AFTER the announcement.

In that sense, if many people believe that USD should appreciate, they usually build their buy-USD positions, so USD could DEPRECIATE by sell-USD trades in the future.

Question:

An intervention by a central bank seems not to work. Why is that?

Answer:

There are too many trades on the opposite side of the central bank due to (1) apparent central bank's trade, forecastable movement, and more attention, (2) low volatility and easiness to expand position, and (3) a central bank as a liquidity provider (supply), other players as liquidity taker (demands).

Markets reflect economic reality like a mirror in the long term; especially currency markets of developed countries are too huge to manipulate it. Nobody can distort it, even central banks. No one can blame on currency movements (e.g., JPY appreciation from Japanese perspective). The problem is economic fundamentals, like deflation of Japan, not markets themselves.

For Japanese (exporting and importing) companies as a whole, USD depreciation & JPY appreciation is not that negative, but JPY depreciation against non-USD, especially Asian currencies like KRW is very important to make a profit. If you look at JPY/KRW rate and Nikkei 225 in and after 2006, you can make sure of it. This is because Japan as a whole is a current account (technically trade balance) surplus country.

Currency markets do not reflect relative "strength" of a country; it is just a conversion rate of two currencies.

Also, a currency's value is on the opposite side of a goods/service value; when a value of goods/service is down (up), then a value of a currency is up (down).

Question: Why is Japan in a deflationary spiral?

Answer: Because individuals and companies are concerned about the future and not confident enough to borrow money, consume, and invest. It is not something financial policy (e.g., quantitative easing) itself can do deal with. It is a structural problem of the social system including regulation/rule, tax, and so on.

The most important thing is bringing cash flow generated overseas to Japan in order to stimulate domestic economy.

Global Currency Market Share (1 day average, April 2013, BIS)

1. USD 87.0%

2. EUR 33.4%

3. JPY 23.0%

4. GBP 11.8%

5. AUD 8.6%

6. CHF 5.2%

7. CAD 4.6%

8. MXN 2.5%

9. CNY 2.2%

10. NZD 2.0%

Total 5.3 trillion USD

Global Currency Pair Market Share (1 day average, April 2013, BIS)

EUR/USD 24.3% 1,298 billion USD

USD/JPY 18.3% 978 (195 in Tokyo, ~20% out of 978)

...

EUR/JPY 2.8% 147

...

Total 100.0% 5,345

Demand and supply in currency markets

How should we decide whether or not a certain flow impacts currency markets? Make sure that it is (1) one-way, (2) proactive, tactical trade, or (3) without or limited hedging (with currency risk).

Expected effects of Quantitative Easing (QE) as a non-traditional financial policy by central banks, in the midst of a zero-interest rate period

(1) A central bank's buying of long-term government bonds makes a long-term interest rate lower.

(2) Banks that sells govt bonds above receive cash and it is expected to invest in risky assets and / or lend to borrowers. ("Portfolio Rebalance")

(3) The more money in the market, the higher inflation rate hike expectation.

Why doesn't Japanese govt yield go up with a concern for the govt's fiscal deficits? Because:

(1) 90+ % of JGB is owned by Japanese commercial banks and lifers, that is, Japanese individuals' bank account.

(2) Japan is a current-account surplus country; when a financial crisis, JPY goes back to Japan (repatriation).

(3) Huge foreign currency reserve (especially USD, ~1.27 trillion USD)

Currencies with high interest rates tend to appreciate when risk-on (stock price like S&P 500) and depreciate when risk-off. It has a high beta to S&P 500 from JPY return perspective. There are three reasons:

(1) natural resource countries' currencies, like AUD, CAD, BRL, and ZAR, which are sensitive to global economy

(2) dynamic financial policy (e.g, AUD)

(3) high growth, current-account deficit, financed by other countries

A good high interest rate, a bad high interest rate

(Nominal interest rate) = (Real interest rate) + (Inflation rate)

or

(Nominal interest rate) = (Real interest rate) + (Inflation rate) + (Financial disaster risk)

The Financial Journal is a blog for all financial industry professionals. This blog has been, and always will be, interactive, intellectually stimulating, and open platform for all readers.

AdSense

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

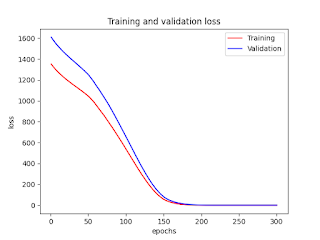

Deep Learning (Regression, Multiple Features/Explanatory Variables, Supervised Learning): Impelementation and Showing Biases and Weights

Deep Learning (Regression, Multiple Features/Explanatory Variables, Supervised Learning): Impelementation and Showing Biases and Weights ...

-

Black-Litterman Portfolio Optimization with Python This is a very basic introduction of the Black-Litterman portfolio optimization with t...

-

This is a great paper to understand having and applying principles to day-to-day business and personal lives. If you do not have your own ...

-

How to win friends & influence people: Part 1 (Influence people and let them move.) Principle 1: Don't criticize, condemn, or ...

No comments:

Post a Comment